Here is the link for the training tomorrow afternoon during the regional conference:

Here is the link for the training tomorrow afternoon during the regional conference:

For innovation to exist, according to George Courous, the development has to be new and better. The innovator’s mindset is that we can develop the thinking that creates new and better ideas.

Since watching the IMMOOC Week Two podcast, I’ve been thinking about the importance of defining what “better” means. In my class, I would feel like I was being innovative if I could increase the number of students engaging in the items from the list below.

One of the things that I wanted was for “better” to be measurable. Here are some aspects that I would like to be able to document, measure and then start to work towards:

Last week, I suggested that we can’t innovate if we are measuring with rubrics; however, it’s important to also know if what we’re doing is actually working. In essence, it’s developing some data to observe.

However, there’s some other aspects to what I’d like to see as “better,” but I don’t think that we can find a way to measure it. For example, if I was working on the above, I’d like to see the students feeling happier and more excited. And, I’d also like to see that the students can transfer more. If they could take the skills and developing intelligence and apply it in other contexts.

Review of the Questions and Embodying the Mindset

It seemed to me in the reading of this chapter, that the questions place teachers directly into having an innovative mindset because we have to be empathetic and reflective to find answers. Moreover, for us to really answer these questions we have to step outside of ourselves as teachers, and critically look at what we’re doing, and be ready to change.

Mainly, those questions ask us question our practice through the eyes of those we teach.

One of my favorite questions, however, comes from the end of Chapter 2 and is in the questions for discussion: If you were to start a school from scratch, what would it look like?

Over the past ten days, I’ve thought about this. Our schools aren’t really laid out for innovation. In my school, most of the hallways are an off-white, industrial color that make everything look the same (it’s actually changing as we have students who are painting murals on the walls). Our classrooms have an industrial feel. Rows of desks and chairs. A teacher’s desk, more often than not located somewhere front-and-center. The floors are pretty much the same color as the walls and are a hard linoleum. There’s obligatory Smartboard and projector. These layouts invite a teacher-centric, delivery, knowledge transfer model approach to lessons. Even when the teacher breaks the row and builds a circle of desks, the teacher is still very much at the center. I’m guessing that most classrooms around in the country, in public schools, look like this.

In our department, with the knowledge that Chromebooks are coming to be part of a 1-to-1 program, we’ve started to talk about removing the furniture and getting new stuff–modular seating, cafe tables and chairs, places to work individually. We’re going to try to create some classrooms that allow for collaboration, comfortable work spaces, small-group meetings. Many of us with a new classroom set up and full-time access to technology hope to create classes that invite learning models that have students creating their own knowledge, making decisions about how to display their learning, and working with others to do so.

However, as I write this, I’m looking back to my copy of the Innovator’s Mindset, and see that question, “Would I want to be a student in my own classroom?” And, I’m realizing that we’ve forgotten to bring in any students to the discussion to get their perspective and ideas. How would I build a school from scratch, well, I have a lot of ideas, but they’re mine.

What if the question we asked was, “If students were going to build a school from scratch, both its physical structure and curricular requirements, what would it look like?” What would kids want in a school? What could we build that would make them want to come?

Furthermore, if I were to construct the curriculum of an innovative school, I would want students to be at the center of the planning. I would like them to think about what the school day would look like, what the content of courses would be, what the outcomes of the school would be, who the teachers were and how they would teach.

One way that we can be innovative in our teaching is to let students make decisions influence the direction of our schools and classrooms.

A scene from Friday morning:

We were all riding a little high at the end of a hot first week of school. Kids were glad to be back. My plans were rolling out pretty smoothly: I had gotten two classes started on creating blogs, one class had started on a gamified, self-paced learning module.

I was in my classroom at the beginning of the day, greeting kids as they filed in, and I pulled out my phone, dropped it into my selfie-stick, and started snapping some picks of my class. That’s when I heard the kids:

“Is that a selfie-stick?”

“Does he have a self-stick?”

“Is he periscoping?” I was.

The students were flabbergasted that I would do such a thing. That I would take pictures of our community. That I would have a selfie-stick. That I would use technology to share the vibrant spirit of the first week.

And, while I was just trying to have some fun and to capture a little of the good feeling of the first week at Canandaigua Academy, and perhaps be slightly innovative, now that I think about it, I wonder. Should any of those thing be so shocking to students that they’d see them as novel?

Anyways, the bell rang, and we got busy with the classroom business.

Then, I got a retweet. Dave Burgess and George Couros were putting together a MOOC on Couros’ The Innovator’s Mindset. A book that inspired me this summer and fueled much of the philosophies I’m working to advance my practice. I read it as I was thinking about writing an end of the first week of school blog post, and something to dovetail with my last post: Innovation for Innovation’s Sake.

I’m excited to join the #IMMOOC. I’m hoping it will build my PLN, continue to develop my ideas around innovation, keep me honest about innovating and making and blogging as we move through the next couple of months. What a gift at the end of the first week of school.

Author’s note: A draft of this blog post was written in early August and has been sitting in my Google Drive for several weeks, with me tinkering with it every couple of days. I’m posting it now, and it still doesn’t feel done. The center isn’t there, and I don’t have the tone right. However, taking a cue from Anne Bradstreet, this blogger to his post says, It’s time to get out there.

What does it mean to fail and how have we come to see failure as something terrible, catastrophic?

Here’s what happened:

After over twelve hours of running, I came into an aid station called Camp 10 Bear. I was tired, but ready to keep going. However, I hadn’t peed for over six hours, even though I had been drinking regularly. I went to for a medical check because I wanted to make sure I wasn’t in the early stage of kidney failure. I got weighed and had my vitals taken. They green lighted me to keep going.

I went to my wife, she helped me change clothes, a new t-shirt, socks. I refueled at the aid station, refilled my pack, said to the volunteer there, as I pointed in a particular direction down the road, “I’m going that way?” to which he replied, “Yep.” And off I went, moving slowly, still munching on a handful of grilled cheese sandwiches.

Forty-five minutes later, after a huge climb, a runner came towards me, yelling, “We’re going the wrong way.” I was off course, on a part of the route that I was supposed to be on, but about 23 miles later. The only thing to do was to turn around, head back to Camp 10 Bear, and see where I was at.

On the way back down, I passed scores of runners coming up the hill, asking if I was okay. All I could say was “I got off route and went the wrong way.” They groaned, vocalizing my pain.

Once back there, completely demoralized and just a few minutes ahead of the cut off, I decided, with tears in my eyes, to drop.

It’s easy in this day and age to seek blame. “It’s not my fault” has become a standard phrase. As you’re reading this, you’re probably saying, the aid station worker gave the wrong directions. However, I firmly believe that in this instance, I’m responsible. I should have known the course better. I should have confirmed before leaving that I was going in the right direction. There are times when circumstances and the larger forces contrive to end our runs and force a decision. This was not one of those times.

In the media, success and failure are at the core of the narrative, especially around sports and athletics. We love the story of triumph after failure, of accomplishment after defeat. We love the come back. The underdog surmounting his or her foes. We don’t often look at failure for what it is, which is the end.

In telling this story over the past month, I try to avoid euphemism as much as possible. I lay it plain–”I went to Vermont, and I failed.” Sometimes I say “epic fail.” But even that I don’t like. I’m not Homer or Milton, and I’m certainly not Achilles or Odysseus. Sometimes failure is small, and in the grand scheme of things, nothing. Sometimes failure is a runner on dirt road watching others keeping going.

When I say that, that I failed in what I set out to do, people twitch. They shake their heads. My dad, kind and good-natured, being fatherly and protecting says, “Most people don’t even think about running 100 miles,” as if to say you did something few others did, isn’t this success? My wife wants to cut me off when I use the word failure. She’ll say, “But you ran more that day than you ever have before.”

To get to the Vermont 100, I had to have a 50 mile qualifier, which for me was the JFK50. I did over 1200 training miles, or what amounts to somewhere between 20 and 30 hours a week. The race fee was $180, with another $150 volunteer buy out. I went through three pairs of running sneakers. Most days I’m either up at four to run before work, or I’m going home after work to run before I need to get dinner on the table. I don’t keep track of the boxes of gel, energy bars, bags of electrolyte drink I take in. I also don’t keep track of the other resources I eat up following these goals: tolls on my family, my knees and ankles.

One way to look at it is that all that’s lost, and that I’ll never get it back. Another way to look at it, is to say, the experiences make you stronger. Is it human instinct to find the smallest element of success to hold onto to keep surviving, and thus to perpetuate the self and its genes? Is this the core of biology, destiny, the Darwinian selfish gene?

This is not to say, in my attempt here at the 100, that there will be no other attempts. I will take on this distance again, either in Vermont or someplace else. Success or failure? I’m still not sure, but I’ll try to figure it out as I look to toe the line again.

Author’s note: While this post needs work. It’ll be used as part of a series of model blogs for students in my English 101 and Media Maker classes this fall as a part of writing and media projects student do on reflective writing and storytelling.

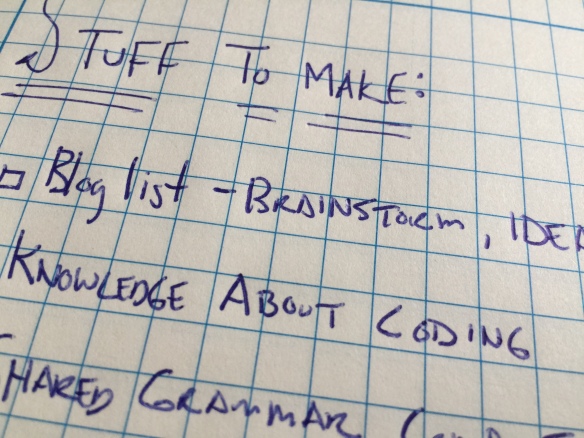

Inspired this week by Katie McFarland’s (@Katiemc827) #slc2016 Maker Challenge, and reading George Couros’ (@gcourcos) The Innovator’s Mindset, I arrived at a major brainstorm, which I’m calling #edmakercamp.

As 21st century educators, we read educational books, create Professional Learning Networks through social media such as Twitter and Pinterest, we attend workshops, we read blogs by other educators who reflect on their practice, we attend edcamps. We spend a great deal of time collecting data and information on educational practice, it becomes and kind of research where we hope that one day we can put it into practice.

Sometimes we do actually find the time to integrate that stuff into our classrooms. We write curriculum in the summer. We spend August creating a new unit. Often, we find ourselves saying, “When I have time.” We spend a Saturdays and evenings writing new lessons or making activities that evolve from our research. But, it’s not easy.

I’m making a call for “#edmakercamp,” and here’s the idea. Pull together a group of your educational besties–those teachers who you work well with, but who will also hold all members of the group accountable for actually doing work and creating. Then, go find a work space–perhaps some classrooms, a computer lab. However, try to get away from it all and find a place for a retreat, a place where everyone can work without interruption. Fill it with laptops, cameras, paper, markers, scanners. Fill it with maker items. Stock it with everything teachers need to create for a day.

Then, fill it with teachers and administrators who are looking to make.

At #edmakercamp, the purpose is to take all the stuff you’ve been reading and learning about with education, and do the stuff you’ve been looking to do.

If you’re in need of time to think about your practice and want to grow through self-reflection, spend time writing and then blogging. Been wanting to make some Schoology resource pages for your department, do it. Looking to retool that unit on “Revolutions” in your Global class. Looking to implement the PBL in the first semester of your IB Biology class, use #edmakercamp to do it.

It’s not a research and learn time. It’s a time to put those thinkings and ideas, and to create the stuff to implement, so in the next day, weeks, months, next school year, you can pull it out and use it.

Use the group. In bringing people together, spend the first part of your edmakercamp to share, discuss. Get ideas out. What are people going to work on. What will be each campers outcome at the end of the day. Use the first part of your time to get the gears primed for work.

But then, stop the talk, and move into work time, and work as a group to be focused. Commit to quiet work time. If you’re working in groups, great, but be focused and assign someone to keep the group on task. You may need to create quiet spaces and semi-quiet spaces. Have all participants decide on a how long this block of time will be, say “We’re going to make for the next two hours.” Set a timer. Then, at the end of the block, come out of it, grab some snacks, share and discuss. Talk about what you made. After a brief rest, back into work time.

Bring to your #edmakercamp some people who aren’t making. Bring some helpers. Some people who can scan items, take pictures. If you need a video file converted, that person can do it. This role could be played by a couple of tech-savy students, or a media specialist who sacrifices his or her work time for the benefit of the campers.

We need time as educators to not only read about innovation, but also time to prepare for those innovations and to create the materials that will be put into practice. We need to give ourselves time to reflect through our blogs and share those innovations with our networks.

You must be logged in to post a comment.